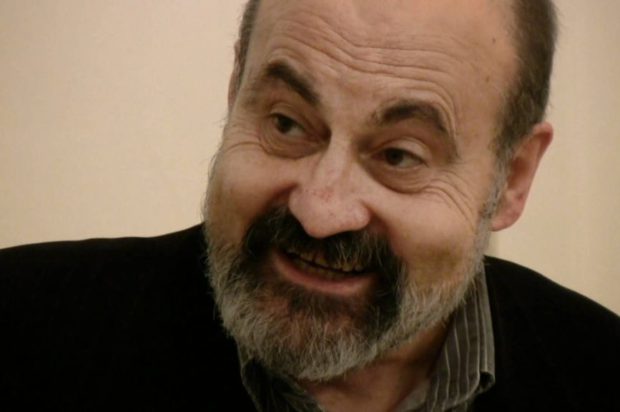

Tomáš Halík nació en Praga en 1948 y fue ordenado sacerdote en Alemania en 1978, en plena Guerra Fría. Actualmente es el párroco de la Iglesia de San Salvador en Praga, al tiempo que responsable de la Academia Cristiana que allí mismo tiene su sede. Su labor pastoral descuella por la gran cantidad de jóvenes que participan de las actividades de esta Academia, en tiempos en que la cultura checa se caracteriza por un alto porcentaje de personas que se manifiestan no creyentes.

Sus antecedentes académicos incluyen una licenciatura en Teología en la Universidad de Letrán en Roma y un doctorado en Sociología por la Universidad de Carlos en Praga. Asimismo ha recibido distinciones en las Universidades de Oxford y Harvard. Fue también galardonado con los premios Guardini (2010) y Templeton (2014).

Entre sus obras se destacan Paciencia con Dios y La Noche del Confesor, traducidos a varias lenguas y reseñados oportunamente en CRITERIO.

Mientras se prepara una traducción de la entrevista exclusiva que será publicada en una próxima edición nuestra revista, se ha preferido publicar su texto original en inglés, que podrán disfrutar muchos de nuestros lectores en Criterio Digital.

IN YOUR BOOK THE NIGHT OF THE CONFESSOR YOU CAN PERCEIVE THE SIGNS OF THE TIMES, THROUGH THE SOULS OF THOSE APPROACHING THE PRIEST FOR ADVICE AND COMPASSION. ¿ HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE THE CHANGES IN THE WORLD’S CULTURAL TRENDS YOU CAN TRACE FROM YOUR OBSERVATION POST IN CENTRAL EUROPE?

A change of civilizational paradigm is occurring not only in central Europe, but also in a large part of the world, and takes the form of social fragmentation. I think that modernity culminated in the cultural revolution of 1968; the left wing student uprisings were suppressed politically, but the “Second Enlightenment” with its resistance to authority changed for good the cultural mentality and also reinforced secularisation in many countries. Modern rationalism also gave birth to two phenomena: advanced technology and the capitalist economy, and these set in motion the most significant social and cultural process of our time–globalisation. A global post-modern (or rather super-modern) civilisation started to emerge. The mutual linkage of different parts of the world provided enormous scope for development, but also brought with it new complications and threats. In my view the fall of communism and many authoritarian regimes was a side-effect of globalisation–regimes with centrally-planned economies, and the censorship of ideas could not hold their own in the free market of goods and ideas. It seemed that liberal democracy would be the political form of the globalised society of the future.

In the course of recent decades, however, another aspect of globalisation has come to the fore and given rise to various forms of resistance to globalisation, in opposition to the West from which the process of globalisation emerged, and in opposition to liberal democracy and its political institutions and elites. Fear of “westernisation” and resistance to it have grown, particularly in the Arab World and Africa. However, even in the West, globalisation has, paradoxically, also sown division, not only between different societies but also within them, a division between those who have profited from globalisation and become richer, and those who have become poorer. That division of society has weakened the middle classes, who were traditionally the standard-bearers of liberal democracy.

A key role is played by new forms of mass communication–people enclose themselves in “bubbles” on social networks, and accept only information that reinforces their personal and group prejudices. Social networks help spread the “liquid anger” of people who feel frustrated and have lost their faith in existing political systems and their representatives, and they are beginning to support populists with dictatorial tendencies. The society that created globalisation finds itself in crisis. The world is becoming fragmented once more and this process is accompanied by the growth of nationalism, religious fundamentalism, and political extremism. Many young people and Christians that I encounter are aware of these dangers but can find no solutions.

EACH CULTURE AND EPOCH CHALLENGE RELIGION IN A PECULIAR WAY. ¿HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE THE DIFFERENT CHALLENGES FACING RELIGION IN EASTERN, CENTRAL AND WESTERN EUROPE TODAY?

In a large part of Europe the process of secularisation continues in the sense that people’s confidence in traditional religious institutions is growing weaker, and they are less and less inclined to let them govern and control their private lives or to participate in the life of those institutions (such as in the form of regular church attendance). However, while the number of those who fully identify with the practice and teaching of the churches has fallen, the number of convinced atheists has not risen. The majority of Europeans can be divided into spiritual seekers on the one hand, and the religiously indifferent (apatheists), on the other. In many countries the number of “former Catholics” or “bad Catholics” (those who have not parted company with Christianity but are very critical of the present form of the Church) greatly exceeds the number of “active Catholics” (“parishioners”). The future of the Church, the future of Christianity, and, to a degree, the future of Western civilisation depend on the extent to which the Church is capable of addressing “seekers”. It is unrealistic to assume that some sort of conventional mission would be capable of winning over the majority of such people, in the sense of squeezing them within the borders of the existing institutional and intellectual structures of the church. It is necessary to open and transcend these borders.

Most probably it will be necessary for the churches to develop a third type of service alongside conventional care of believers in parishes, and alongside conventional missions, namely, “accompanying believers”–in the spirit of dialogue, mutual respect, and mutual enrichment. It is necessary to take the path of sharing experiences and charismas without proselytism. This needs courage, but even Abraham, the “Father of the faith” set out on his journey without knowing where it would lead.

Nor can “apatheists” be written off. They too often have something “holy” in their lives. We should behave like Jesus on the road to Emmaus: first listening silently for a long time and paying careful attention to peoples’ questions and worries, before starting to share and interpret the stories entrusted to us.

¿HOW WOULD YOU CHARACTERIZE THE PRESENCE AND LIFE OF ISLAM IN THE WORLD AND IN EUROPE IN PARTICULAR?

As I said before, fears have been growing in the Arab and African world that globalisation brings with it westernisation and the loss of their own cultural identity. The efforts of dictators, such as the Shah of Persia, Saddam Hussein or Qaddafi, to secularise society, supported by the West and the Communist East, aroused resistance and led to their downfall, starting with, Khomeini’s revolution in Iran. For some radical political currents, Islam became a political ideology defending ethnic identity, and those efforts developed into open war against the West in the form of terrorist attacks. The radical ideology of jihadism found fertile soil even among some of the second and third generations of immigrants in western countries, and even among sections of frustrated youth in the West–people, whose families could not help them create their own personal identity, who seek “a collective identity” in extremist groups. It is absolutely necessary to distinguish clearly between Islam and Jihadism. So long as people in the West (egged on, in particular, by populist politicians) continue to express opposition not against Jihadism but against Islam as such, they will encourage the propaganda of the Jihadists, whose aim is to convince the entire Muslim world that the West is hostile not only to the Jihadists, but to Islam as such, and to all Muslims, and therefore must be destroyed. In the dialogue between Islam and the Western liberal world–a dialogue that is vital for the world’s survival–the church has a major role to play and has an enormous scope because it shares many values with both those worlds, which are incapable of understanding each other. I highly value the stances taken by Pope Francis and his efforts in this field.

¿COULD YOU SHARE WITH US YOUR VIEWS ABOUT THE MAIN ISSUES THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT IS FACING NOWADAYS?

I hope that the anniversary of the Reformation will help deepen awareness that Christianity exists in three mutually compatible, mutually complementary, and mutually enriching forms: the Latin tradition of Rome, the tradition of Eastern Christianity, and the tradition of the Reformation. “Catholicity” is a eschatological goal towards which all three currents must journey in mutual brotherhood and mutual support. I think an inspirational model can be found in the coexistence of various monastic communities with different accents in terms of spirituality, theology, and practice. What would the Catholic church look like if the Jesuits said that the Franciscans no longer had a place in the church, or if the Franciscans said the same about the Jesuits? In the personality of Pope Francis we can see that a fruitful synthesis of those two traditions is possible, in a single person even! Many of my Protestant friends tell me they are no longer “Protestants”, because they no longer have any need to protest against a Pope like Francis. Pope Francis has become an inspiring moral and spiritual authority transcending not only the frontiers of the Christian churches, but also the frontiers of Christianity. He represents hope and inspiration for “people of goodwill”, whatever their cultural roots.

¿WHAT SIGNS COULD YOU TRACE COMING FROM THE HUSITE TRADITION IN CZ?

In the Czech Republic, a minority of the population openly declares adherence to Christian churches, but 90% of that minority are declared members of the Catholic Church. The Protestant churches and the small and ageing “Czechoslovak Hussite Church”, which emerged from Catholic modernism after World War I, represent a small minority. Nevertheless John Huss and Hussitism are among the nation’s traditional symbols. However it is necessary to distinguish between Huss as a moral person (one who is respected by many Catholics) and Hussite theology (which is little known by now), on the one hand, and Hus as a symbol, on the other. Various historical epochs projected onto that symbol its ideals – in the 19th century they turned him into a nationalist, while the Communists made a social revolutionary of him. The misuse of Huss and Hussitism by Communist ideology did great damage to the awareness of the younger generation of Czechs. Of interest from the purely theological point of view is the moderate current of later Hussitism, known as Utraquism, which survived for several centuries in fairly peaceful symbiosis and tolerance. In many respects (such as the liturgy and its understanding of the dignity of the laity) it presaged the reforms that were eventually accepted by the Catholic Church at the second Vatican Council. The period of tolerance was interrupted by the 30 Years War, which started in Bohemia in 1618 and proceeded to devastate and divide Europe.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE THE MAIN FEATURES THAT CAN BE SPOTTED IN THE LIFE OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH TODAY? ¿WHAT HAVE BEEN THE MAIN CHANGES THAT CAN SO FAR BE PERCEIVED IN THE WAY THE CHURCH IS RUN BY A POPE COMING FROM “THE END OF THE WORLD”?

Although Argentina, Brazil and the whole of Latin America are a long way from Europe we don’t perceive them as “the end of the world” – it is obvious to us that the heart of the Catholic world is now located there. I was delighted by the election of a Latin American and a Jesuit (and I immediately commented on it on Czech TV), and my enthusiasm and warm affection are growing all the time as I observe the reformist, ecumenical and inter-religious initiatives of this pope, who has already outstripped his two great and honourable predecessors in terms of his significance for the Church and for the world of today. My only fear is that the response to Pope Francis’s words and actions might remain superficial idolatory of a “smiling, progressive and unassuming pontiff”. Just as the reforms of the 2nd Vatican Council “did not fall straight from heaven”, but were the end result of the work of entire generations of outstanding theologians, so also Pope Francis’s efforts at reform need intensive and profound intellectual and spiritual support. I personally not only pray constantly for the pope (as he constantly asks us to, and as he also asked me to during our brief meeting during a mass audience on St Peter’s Square, to which I was invited after I received the Templeton Prize). I feel a duty to bring together theologians, philosophers and sociologists from different countries for further reflection on Pope Francis’s reform impulses; I have spoken about it with many theologians, social scientists and bishops not only in Europe, but also in the USA, Australia, Asia and Africa. I have managed to put together an international team, which, with the support of the Templeton Foundation, is working on a research project “The Future of Religion in Respect of Central and Eastern Europe”, and as I have been elected Vice-President of the Council for Research in Values and Philosophy in Washington, I have proposed expanding this research project in coming years in cooperation with that international institution. Pope Francis deserves not only prayerful support but also the systematic intellectual work of specialists in various fields, so that his impulses receive further reflection and development in order to put them into practice. A living spiritual and intellectual movement needs to come into existence to undertake the task of developing the reform ideas and impulses of Pope Francis and contributing to the reform and vitality of Christianity and its mission in today’s world, in the way it was achieved by the followers of St Francis and St Ignatius.

¿WHAT OTHER CHANGES WOULD STILL BE NECESSARY?

John Paul II and Benedict XVI brought to a dignified end a long chapter in the history of Christianity. With Pope Francis a new stage is beginning. Or to put it more cautiously: it could begin in certain circumstances. The main theme of the previous epoch was coming to terms with modernity: it was a matter of not accepting modernity uncritically, of not being absorbed into it, but on the other hand, not being determined negatively by modernity, and not creating a “counter-culture”. The Church often fell prey to the opposite extreme. For instance, the over-emphasis on sexual morality was a knee-jerk reaction to the sexual revolution of the 1960s – and understandably it provoked the reaction: you’d better look closer to home! There followed the unearthing of sexual scandals. The church that turned the sixth Commandment into the First Commandment became labelled a sexually perverse institution. But now confrontation with modernity, which is now finished, is no longer a living issue. The main theme are problems linked with the process of globalisation and various reactions to it. Pope Francis has laid fresh emphasis on what found itself overshadowed: charity, solidarity, responsibility for creation, cultivation of conscience, the courage to be creative. If we discover anew the deep roots of Christianity we can be free in relation to the modern and post-modern world, we do not even need to create a “counter-culture” or accept uncritically the ambient culture; we can enrich the world with the newly discovered power of the Gospel.

In today’s world the “dwellers” are rapidly on the wane while the number of “seekers” is growing. I repeat: the future of the Church depends on the extent to which it will be capable of appealing to seekers. The Church continues to concentrate almost entirely on dwellers (traditional pastoral activity), and in some cases efforts to turn seekers into dwellers as rapidly as possible. But alongside those two forms of service it will be necessary to develop a third – “accompanying seekers” in dialogue and with respect, to realise that living faith is a journey, that we ourselves are still “seekers”, that the Church is a “communio viatorum”, a pilgrim community. As a “legacy of the fathers” passed on mechanically, Christianity lost its social and cultural biosphere and no longer has roots and vitality. To be a Christian nowadays, and stand the test as a Christian in today’s world requires three things in particular: first, “launching out into the deep”, developing the art of a spiritual life, a contemplative search for God’s presence in one’s own life (“finding God in all things”), second, educating oneself in the faith, thinking through one’s faith to make it compatible with one’s education and world view, finding an appropriate language with which to witness to one’s surroundings about it in a comprehensible way, and third, bearing witness to one’s faith by moral behaviour in society, creatively incorporating the Gospel into one’s civic attitudes. Christian institutions, parishes, monastic communities, movements, etc., should take as their example the ideal of the mediaeval university, which was a community of life, learning and prayer, a place where people sought truth through free discussion and were mindful of the principle “contemplata aliis tradere” – handing down to others the fruits of our contemplation.

When we contemplate the thinning ranks of priests and the alarming situation in many countries where for many believers the celebration of the Eucharist is not readily available, it would seem that bold measures are called for, such as making up the numbers of priests with “viri probati”, time-proven married men, and opening diaconal service to women and not wasting their charismata. It is important that such ideas are not taboo to Pope Frances.

¿WHICH VALUES PRESENT IN CHARTER 77 HAVE BEEN ACHIEVED AND WHICH ARE STILL MISSING TODAY?

The movement of dissent against the Communist regime, which issued the Charter 77 manifesto, brought together various currents of the opposition – proponents of liberal democracy, Christians and left-wing intellectuals who had broken ties with the Communist Party. That movement reminded me of the stance of early Christians concerning slavery – the Christians did not organise violent uprisings like the revolt of Spartacus, but altered the climate of inter-personal relations so that slavery was no longer possible in the long term, because the slave was now a brother – let us recall Paul’s letter to Philemon. Charter 77 did not call for a revolution but for citizens to start to behave as free people in conditions on non-freedom. It called on the regime to take seriously the laws it had promised to respect in the framework of international conventions. The major figures of the Charter – particularly Václav Havel, with whom I was linked by forty years of friendship – subsequently became the figureheads of the victory over Communism and the restoration of democracy in the 1990s. Sadly, two of Havel’s successors in the office of President, Václav Klaus and Miloš Zeman, embody a diametrically opposite political philosophy and are now part of the wave of populism washing over the post-Communist part of Europe, and are numbered among such problematic politicians as Orbán in Hungary and Kaczyński in Poland. However, for young people and for pro-Western, pro-European and democratically-minded intellectuals, Havel and the ideals of Charter 77 are still a source of inspiration, even though we live in different times.

¿WHAT EXPERIENCES FROM THE “CHRISTIAN ACADEMY” COULD BE INSPIRING FOR OTHER CULTURAL MILIEU?

The Czech Republic is considered to be one of the most secularized countries of the world. I am very glad that God has placed me in a situation where faith is not something to be taken for granted. We have placed to much emphasis on whether people believe in God and neglected a far more important question: what God do they believe in? Many people who regard themselves as atheists in reality reject only a pathological caricature of God – and I fully agree with them. I am responsible for two institutions in the Czech Republic: the Czech Christian Academy and the Academic Parish in Prague. Here we try live the model of the church that I spoke about: seeking together through free discussion. We try to be creative, and particularly to link contemporary culture and art – contemporary art is for us a medium that articulates questions to which we try to find answers. During the 27 years since the fall of Communism there have existed lively centres of the Czech Christian Academy in every larger town throughout our country. In the Prague academic parish, some 1,500 adults – people with higher education – have joined the Church and been baptised after almost two years of catechetic preparation. The numbers of those seeking baptism and attending mass are rising every year. An essential part of our pastoral activity consists of spiritual exercises, and introduction to the art of contemplation and a contemplative attitude to life.

Yes, even this is possible in the centre of a country where many churches are empty and where the smallest percentage of the population declare membership of the church. Yes, it is necessary to ask believers and non-believers what God they believe in and what God they don’t believe in. And to show them that the God spoken of in the Bible leads to the path of liberation.

In my theological work I have set myself the task of creating a new socio-theological discipline – “kairology”, contemplative “reading the signs of the times”, a theological hermeneutics of contemporary culture and society. God speaks to us not only through Scripture and tradition, but also through the events in today’s world. We must listen carefully to what He is saying and interpret it responsibly.